Last week, we talked about the giant monsters stomping across screens and crushing innocent civilians, feeding the spreading panic of the brewing Cold War. As a result, horror fans and creators alike were left with many questions and fears to address, especially when it came to the Red Scare. We’ve already established in this horror cinema crash course that a piece of horror media/art is a response to society at the time of its creation, often resulting in monsters, but what happens when the greatest fear is your very own neighbor?

When World War II ended, Russia allied with East Germany, leaving them to live under the current Soviet communist rule, which the United States saw as a personal attack. Not only was it personal, but it was a threat to their free lives. If communism could take over East Germany that quickly, what was to stop it from taking over the Land of the Free?

People like Senator Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin took it as their personal mission to protect the American public from the looming threat of Communism. Because of his early 50s crusade to expose and hopefully legally try individuals without sufficient evidence to back up his claims, an entire era and term were named after him: McCarthyism.1 McCarthyism was the boogeyman of the early 50s, the eternal threat to people’s lives and reputations. At any moment, someone could be accused and/or punished for their true, or false, ties to communism. Lucille Ball, America’s comedic sweetheart, was publicly accused of being a communist in 1953 and had to fight for her reputation and career because of it.2 If someone as public and loved as Lucy herself could potentially be a communist, who else was hiding in the Soviet shadows?

Witch hunts weren’t new in the 1950s by any means, but the televised and broadcasted public accusations available for the world to witness now were. The fear of another war, especially with the new introduction of atomic weapons, was palpable. No one wanted to believe that another war could be possible, and a war with weapons that could decimate millions in one swoop was terrifying. The Iron Curtain’s ever-present reminder that the world had no idea what was going on behind its borders caused mass hysteria, especially in America.

Horror movies in this period began to shift towards the Science Fiction genre, introducing both giant monsters that could destroy huge populations, and invasive, brilliant, and destructive beings capable of mind control. Aliens were all the rage in the 1950s, and still are in many ways. Between 1948 and 1962, it’s estimated that nearly 500 sci-fi feature films and shorts were made and distributed, making it the most widely consumed film genre post-war. That’s roughly 35 films made per year—an astronomical number for that time period.3

But why Sci-fi? Science fiction, according to Victoria O’Donnell, “is about the scientific possibility that explores the unknown” and “both warns against and applauds the advance of science and technology while it consistently considers the problems and possibilities posed by meeting the new and unexpected, the alien.” People were both in fear and awe of science's possibilities and dangers, and of the scientists who pulled the strings. Few things had a greater real-time significance than the threat of a science-backed invasion by an outside threat. Were they peaceful, or did they want to destroy and conquer? No one knew.

The alien itself was a representation of the unknown. For the Americans, it represented the Soviets, people possessing secret technical and scientific knowledge foreign to us, and whose intentions were unknown. Did they really come in peace as many cinematic aliens of the 50s said, or did they have other motives? No one could be sure, and the Americans weren’t ready to take any chances.

Secrecy is one of the most common themes of Sci-fi alien films. In almost every instance, the military, government, scientists, or all of the above, kept vital information from the public or extra-terrestrial intruders. The existence or truth of something is almost always kept a secret by those in positions of power, who assume they are protecting the safety of both themselves and the world. But what if an alien really does come in peace?

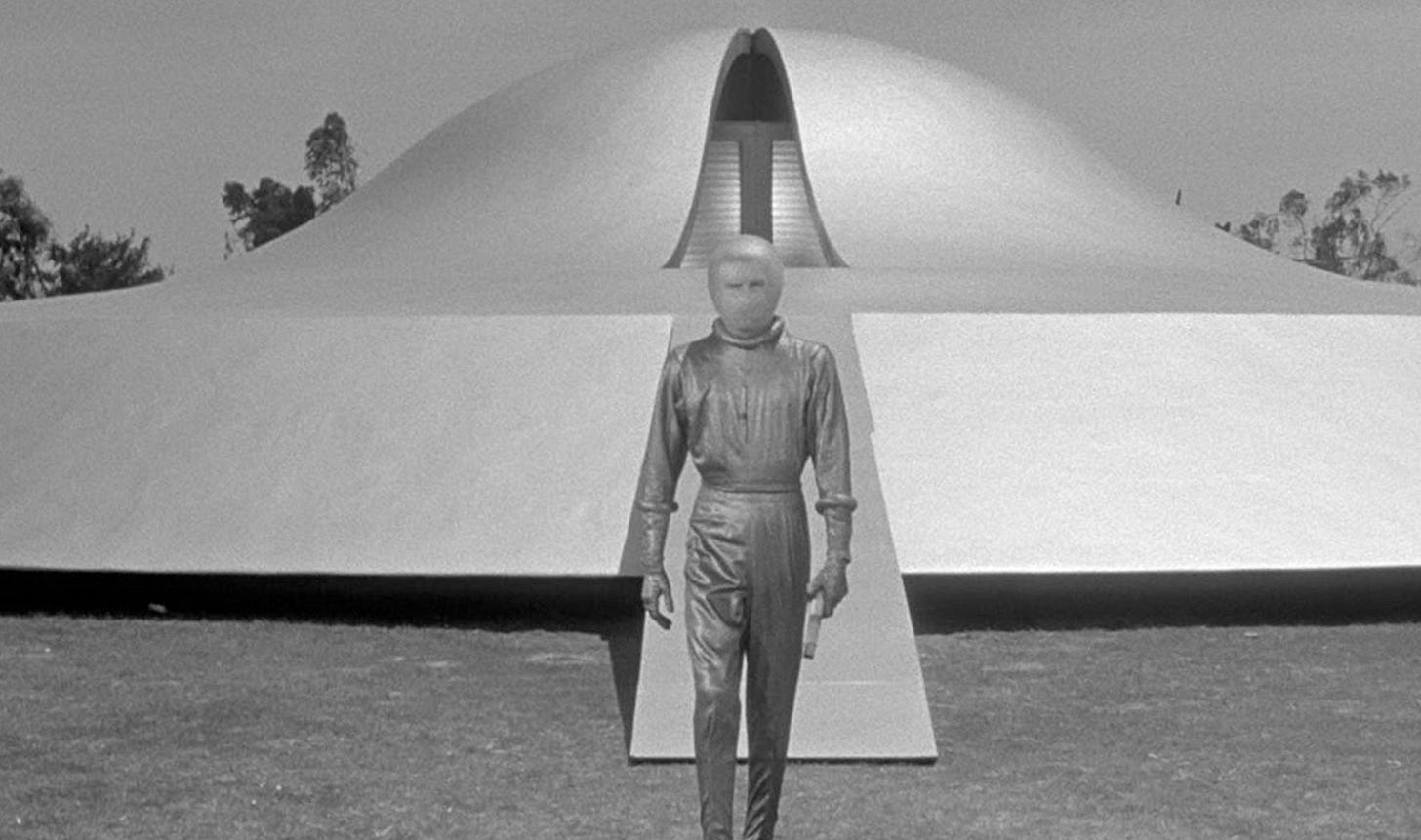

One of the most on-the-nose Sci-fi films of yore is the 1951 film The Day the Earth Stood Still, in which an alien visitor comes to Washington, D.C. to warn the government and people in light of the impending Cold War nuclear threats. Klaatu, the alien visitor, tells them that peace must be their course of action, and if they continue to choose violence and war, they’ll be obliterated. Pure fiction, right?

Science, as O’Donnell put it, “is always related to society, and its positive and negative aspects are seen in light of their social effect.” Think about it—in the last few years, the public has viewed science as both a liar and a savior in light of COVID-19 (deep breaths, we’re not debating COVID conspiracies, it’s okay). Were the scientists telling us the truth, or were they lying? The public couldn’t agree, but regardless of people's beliefs, science and quick thinking saved lives. The overall discourse around those researchers and scientists has shifted since the early days of the pandemic, just as the discourse shifted around scientists immediately post-war. Contrary to many of the anti-scientist beliefs of the 40s atomic bomb era, the 50s Cold War scientists might have been the only hope in surviving a potential attack, and the people knew it.

Overt alien invasions weren’t the only type of Sci-fi films made in the 50s. Films portraying covert invasions were often more popular because of their intentional or unintentional political subtext. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is one of the best examples of covert invasions. You may have heard the term “pod people” before, but you might not know the reference is from this movie. The pod people of the film were once everyday individuals, going to work, church, school, and the grocery store—until they were replaced with soulless, emotionless carbon copies of themselves. The body snatchers were grown in pods from alien plant spores landing on Earth, and have identical features, memories, and personalities to their copies. While peacefully sleeping, the real town members are replaced with their pod-grown body snatcher until all but one couple are gone.

Since its release, many critics have likened the pod people to views on communist sympathizers and the potential for it to hide in your very own neighbors.4 They may look like the Bob and Jane that you know, but inside, their American sensibilities and emotions have been replaced with Soviet propaganda. The hysteria of the main character has been compared to the hysteria of the McCarthy era witch hunts, and the film’s overall message has been likened to the espionage and secrecy enveloping the Soviets and the Cold War era itself. Was anyone safe from the subtle subversion of communism if body snatchers took over you while you slept?

The overall theme of the 50s alien flicks is that if the American people banded together to fight against their invaders, be they communists or aliens, they would overcome. If they could do that and stop trudging down the same never-ending warpath, like Klaatu said, they, too, could live in peace. They just might have to face some space monsters first.

Next week, the father of the modern horror film, Hitchcock, is making his debut with Psycho. Are you ready, Norman?

Subscribe below to get more updates on horror film history leading up to Halloween, and soon I’ll tackle one subject at a time to give you the run-down on the most terrifying tales through the ages.

Are you scared yet?

More on McCarthyism and more on McCarthy and the Red Scare (what a guy)

A lot of my background information for this article came from the anthology “The Fifties: Transforming the Screen 1950-1959” by Peter Lev. In it, he includes many different scholarly articles (like O’Donnell’s called “Science Fiction Films and Cold War Anxiety”) about film in the 1950s, but there are several other books that go through other decades (the series is called “History of the American Cinema”). I’ll most likely use others in the future, thanks to my dad and brother both being film people who have academic resources for me. Thanks, guys.

This BFI article was an interesting read about the history of Pod People

I was reading this feeling like it was out of sync, and I somehow missed the email…nope! This was a far earlier post I never got to respond to. Hat tip to Substack for nudging me toward it one month later.

The thought that struck me here was how strange it is that these defining genres of my life weren’t always out there. I mean, there was horror and science fiction in literary forms, but I take for granted that these tropes and approaches started somewhere, with one filmmaking team making decisions that would reverberate across the decades that followed. It’s powerful to think about their influence that way, but it’s also powerful to consider than decades from now, people might look at “I Saw the TV Glow” or “Hereditary” as the first lightning strikes of new wrinkles in the genre.

I tend to think of history as having been made (past tense), but reading this today got my brain churning about it also might well be in the works today.

In any event, I continue to appreciate learning the backstory for one of my favorite genres, even when I respond a little out of sequence.